A reusable vest that can map the electric impulses of the heart in fine detail could detect abnormalities from a potentially fatal heart disease much earlier than is currently possible, suggests a new study led by UCL researchers.

The study, published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, found that an electrocardiographic imaging (ECGI) vest, developed by Dr Gaby Captur at UCL, could detect electrical changes associated with an inherited heart muscle condition at a stage when standard tests do not pick up signs of disease.

The condition, called hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, is where the muscle wall of the heart becomes thicker and stiffens, affecting how well the heart can pump blood around the body. It affects an estimated one in 300 adults.

While often people with genetic variants that cause the disease have no symptoms at all, the condition can lead to heart failure and is frequently cited as the most common cause of sudden unexpected death in young people.

Lead author Dr George Joy (UCL Institute of Cardiovascular Science and Barts Heart Centre) said: “By finding subtle electrical abnormalities using our new technique, we are able to detect hypertrophic cardiomyopathy earlier. This is important as it means we can potentially act earlier, providing new treatment to slow the disease as well as fast-tracking individuals to clinical trials that have potential to stop the disease entirely.”

“Next steps of the research include repeating these results in a larger group of patients and following individuals over time to see how these early electrical changes affect the risk of life-threatening heart rhythms later on.”

The ECGI vest has 256 sensors rather than the 12 used in a standard electrocardiogram (ECG) and can provide detailed electrical mapping of the heart in just five minutes.

Previously, this kind of detailed mapping was rare – either requiring a catheter to be inserted inside the heart cavity or using single-use devices that were costly and time consuming to set up. The ECGI vest is also reusable and so has potential to be used as a standard screening tool.

The new study looked at 174 patients whom had genetic testing (overseen by Dr Luis Lopes, UCL) recruited from three London hospitals (Barts Heart Centre, St George’s Hospital and Royal Free Hospital), including 37 healthy volunteers. Patients included people who already had hypertrophic cardiomyopathy as well as individuals with disease-causing genetic mutations who did not have overt signs of the disease.

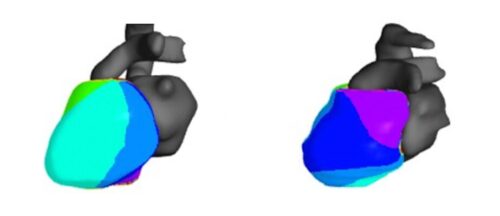

The team found that the ECGI vest identified electrical abnormalities among 1 in 4 individuals with a gene mutation for whom no signs of disease were detected via either cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) performed at the Chenies Mews Imaging Centre, the highest standard of heart imaging, or a 12-lead ECG, the typical way the heart’s electrical activity is assessed.

In particular, these patients were found via ECGI to have an uneven pattern of electrical signal recovery and slowed conduction of electrical signals through the heart.

The researchers also applied a machine learning model to the results of 12 markers from the ECGI vest in order to grade the severity of disease and estimate risk of sudden cardiac death.

They found this grading matched the risk estimated using standard protocol, which is based on information such as age and certain structural features of the heart.

Dr Captur (UCL Institute of Cardiovascular Science and the Royal Free Hospital, London), who was senior author on the latest study, said: “The ECGI vest we have developed is expanding our ability to understand the electrical functioning of the heart and to assess more precisely people’s risk of developing life-threatening heart rhythms.

“People who have genetic mutations causing hypertrophic cardiomyopathy are monitored regularly and given advice around exercise. In some cases, this might be to reduce or stop any intense exercise. This prescription can have huge impact on a person’s quality of life, particularly in athletes or young patients. By better understanding risk we hope to avoid instances where people are given such advice unnecessarily.”

The study was supported by the British Heart Foundation, National Institutes of Health and Care Research (NIHR), Medical Research Council, and NIHR Biomedical Research Centres at UCLH and Barts Health NHS Trust.