Congratulations to Dr George Joy from the Chenies Mews Imaging Centre, who has had his ground breaking research into the use of novel MRI methods for the early detection of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) published in the journal Circulation. The paper can be accessed here.

The press release from the British Heart Foundation, who funded the study is as follows:

Combining two types of heart scan could help doctors to detect the deadly heart condition hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) before symptoms and signs on conventional tests appear, according to research funded by the British Heart Foundation. The team behind the study, published today in the journal Circulation, say it offers an unprecedented opportunity to improve treatment for the condition at the earliest stages.

Being able to detect HCM earlier than ever before will also assist trials investigating gene therapies and drug treatments aimed at stopping the disease developing in those at risk.

HCM is an inherited condition that affects around 1 in 500 people in the UK. It causes the muscular walls of the heart to become thicker than normal, affecting how well the heart can pump blood around the body. It is a leading cause of heart failure and sudden cardiac death.

Researchers from University College London, Barts Heart Centre and University of Leeds studied the hearts of three groups: healthy people, people who already had HCM, and people with an HCM-causing genetic mutation but no overt signs of disease (no heart muscle thickening).

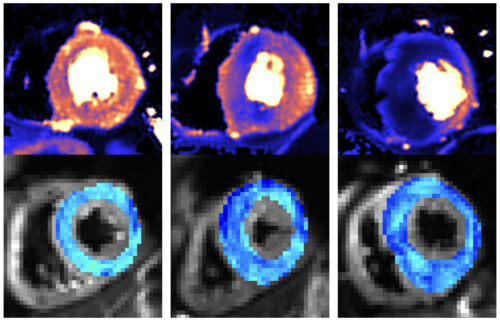

To do this, they used two cutting edge heart scanning techniques. Cardiac diffusion tensor imaging (cDTI), a type of MRI scan that shows how individual heart muscle cells are organised and packed together (the heart’s microstructure). And cardiac MRI perfusion (perfusion CMR), which detects problems with the small blood vessels supplying the heart muscle (microvascular disease).

The scans showed that people with overt signs of HCM have very abnormal organisation of their heart muscle cells, and a high rate and severity of microvascular disease compared to healthy volunteers.

Crucially, the scans were also able to identify abnormal microstructure (muscle cell disorganisation) and microvascular disease in the people who had a problematic gene but no symptoms or muscle thickening. They found that 28 percent had defects in their blood supply, compared to no healthy volunteers. This meant that doctors were able to more accurately spot the early signs of HCM developing in patient’s hearts.

The first drug to slow HCM progression – mavacamten – has recently been approved for use in Europe and will allow doctors to reduce the severity of the disease once symptoms and muscle thickening have appeared. Genetic therapies are also in development, which could prevent symptoms entirely by intercepting HCM development at an early stage.

Perfusion CMR is already being used in some clinics to help differentiate people with HCM from other causes of muscle thickening. The researchers think that these revolutionary new therapies, combined with cDTI and perfusion CMR scans, gives doctors the best ever chance of treating people at risk of HCM early enough that the condition never develops. This would free many families from the torment of seeing their loved ones lives blighted by these devastating conditions.

Dr George Joy, Clinical Research Fellow at University College London, who led the research with Professor James Moon & Dr Luis Lopes, said:

“The ability to detect early signs of HCM could be crucial in trials testing treatments aimed at preventing early disease from progressing or correcting genetic mutations. The scans could also enable treatment to start earlier than we previously thought possible.

“We now want to see if we can use the scans to identify which patients without symptoms or heart muscle thickening are most at risk of developing severe HCM and its life-changing complications. The information provided from scans could therefore help doctors make better decisions on how best to care for each patient.“

Professor Sir Nilesh Samani, Medical Director of the British Heart Foundation, said:

“Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is an inherited condition that is diagnosed in thousands of people in the UK each year. As it progresses HCM can lead to heart failure and increase risk of sudden cardiac death.

“This research shows that the very early changes in the heart caused by HCM can now be picked up by before changes are visible to the naked eye. This is important because in the future, as new treatments become available, this may allow the condition to be treated at a stage before irreversible changes have happened.“

About the British Heart Foundation

It is only with donations from the public that the BHF can keep its life saving research going. Help us turn science fiction into reality. With donations from the public, the BHF funds ground-breaking research that will get us closer than ever to a world free from the fear of heart and circulatory diseases. A world where broken hearts are mended, where millions more people survive a heart attack, where the number of people dying from or disabled by a stroke is slashed in half. A world where people affected by heart and circulatory diseases get the support they need. And a world of cures and treatments we can’t even imagine today. Find out more at bhf.org.uk